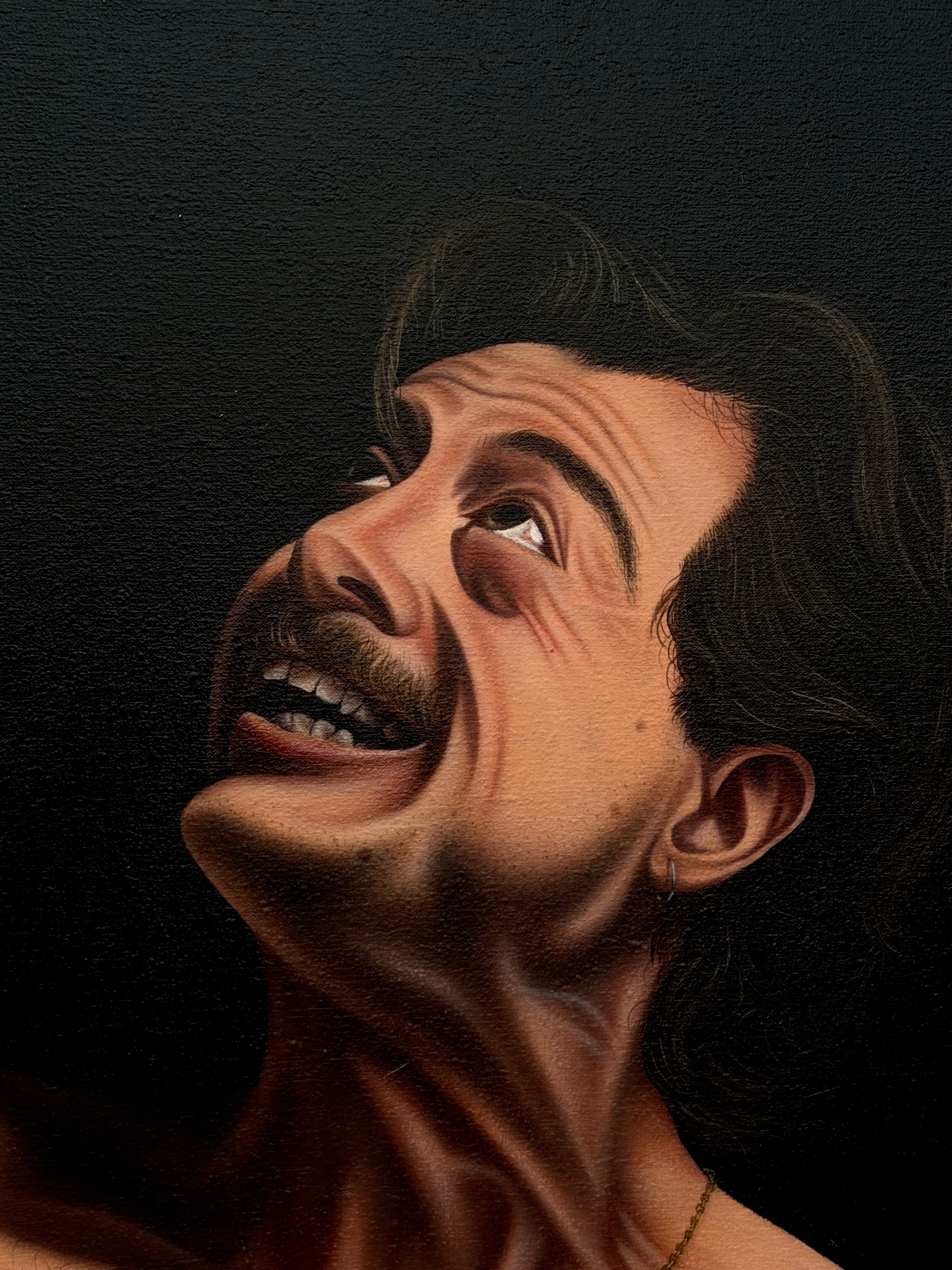

In Glen Pudvine’s The Church of Self, the male body is not merely depicted — it is performed, mirrored, magnified and, ultimately, laid bare. His Frieze London presentation with Xxijra Hii stands as one of the most affecting and unsettling highlights of the fair: a mirror-lined chamber housing a series of hyperreal, Caravaggio-inflected self-portraits in which Pudvine poses like a devotional icon, not as hero, but as struggler.

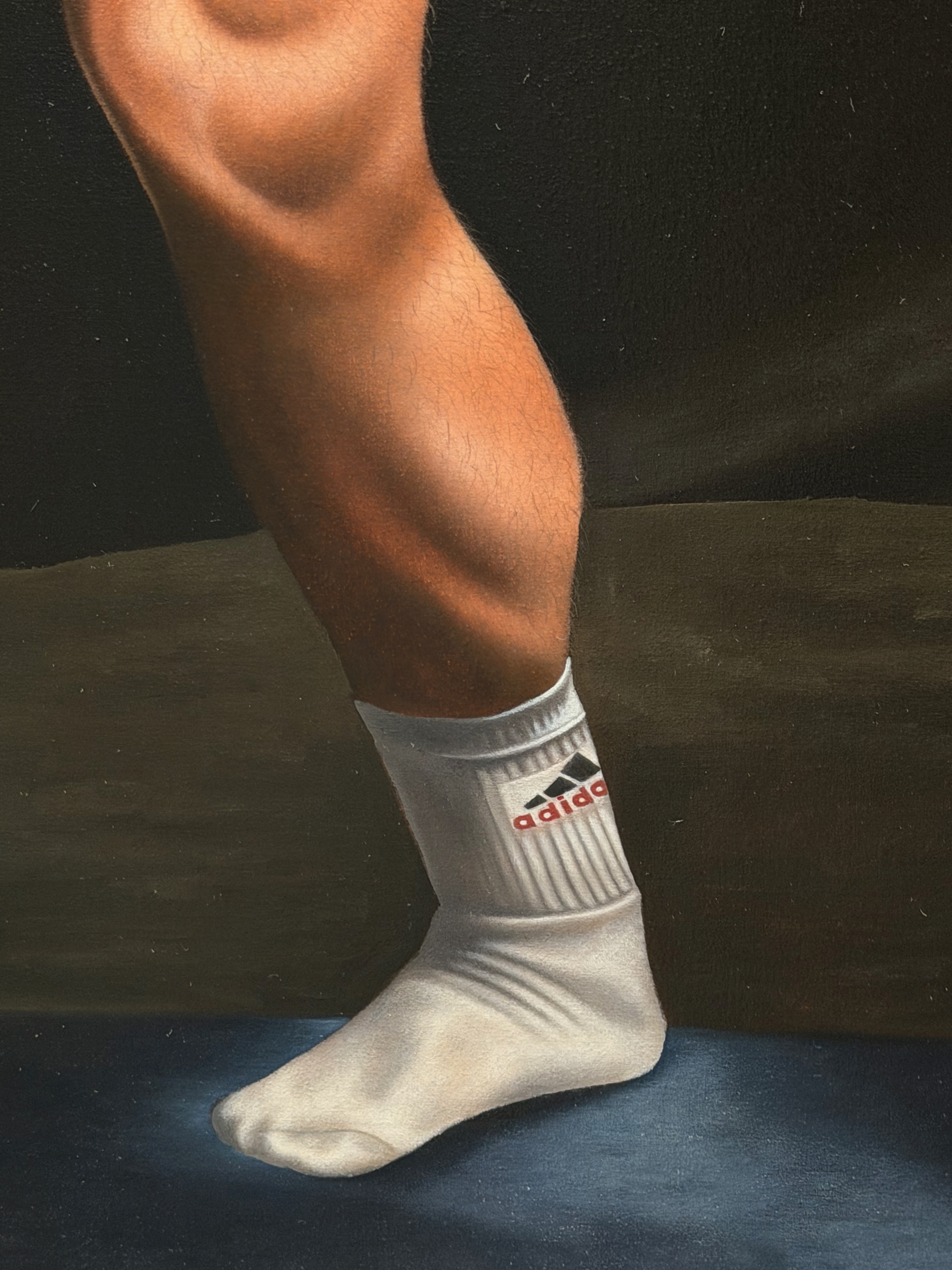

The paintings are obsessive in their surface — each follicle of body hair, each bead of sweat, each tremor of strained muscle is rendered with forensic intensity. This precision is not neutral. It echoes the daily rituals of masculine self-discipline: the mirror check at the gym, the careful grooming, the endless scroll of perfected bodies on screens. Pudvine’s painted figure doesn’t just stand in for the male body — it becomes a cipher for how the male body is constructed, rehearsed, and surveilled in contemporary culture.

“Pudvine’s work doesn’t offer escape, but it does offer recognition. In the infinite mirrors of The Church of Self, we find not an ideal, but a fracture — and in that fracture, the possibility of something more human.”

The upward gaze — repeated across several works — evokes both piety and desperation. It is the gesture of a supplicant, but also of someone trapped in an infinite loop of self-improvement. Pudvine frames masculinity not as a stable identity but as an ongoing performance, an “acting out” of what the male self might be, should be, or wants to be seen as. His gym-toned poses reference both the aesthetic of Renaissance martyrs and the language of fitness influencers, collapsing the sacred and the algorithmic into one.

Around the paintings, mirrored walls distort the viewer’s own reflection. It is impossible to look at the work without also seeing oneself — folded, stretched, warped. In that distortion lies a truth: masculinity today is never experienced in isolation. It is mediated by reflection, surveillance, and comparison. The mirror becomes both seduction and critique: the site where ideals are staged and where they fall apart.

This is a body on display — a male body as object, as icon, as brand. Pudvine deftly situates this within the lineage of the male nude: from Caravaggio’s saints to the glossy, filtered images of contemporary gym culture. But where the classical male body often stood as a monument to idealised strength, Pudvine gives us the opposite: vulnerability and strain rather than triumph. Flesh, not fantasy.

Hair — rendered with meticulous devotion — plays an understated but potent role. For many men, hair is both a marker of identity and a site of daily management. To shave, to trim, to style is not only grooming but a form of self-construction: the mirror as both confessional and stage. Pudvine’s hyperreal surfaces amplify this ritual, exposing how masculinity is built through endless acts of control, repetition, and reflection.

His project speaks to a wider cultural unease. In a digital economy where the self is brand and the body is product, the pressure to perfect is relentless. The gym becomes temple, the selfie a liturgy, and the algorithm the high priest. Pudvine doesn’t mock this condition — he inhabits it, embodies it, and exposes it. By pushing self-representation to devotional extremes, he turns personal vulnerability into a shared encounter.

This exhibition is not just about looking at a male body. It’s about looking at the structures that produce and circulate that body. It’s about recognising how identity — particularly male identity — is constantly performed under the gaze of both others and ourselves. Pudvine’s work doesn’t offer escape, but it does offer recognition. In the infinite mirrors of the Church of Self, we find not an ideal, but a fracture — and in that fracture, the possibility of something more human.

Text and Photographs by Joe Madeira

Links